we interrupt

Nov. 12th, 2025 10:09 pmYour normal programming for a brief announcement:

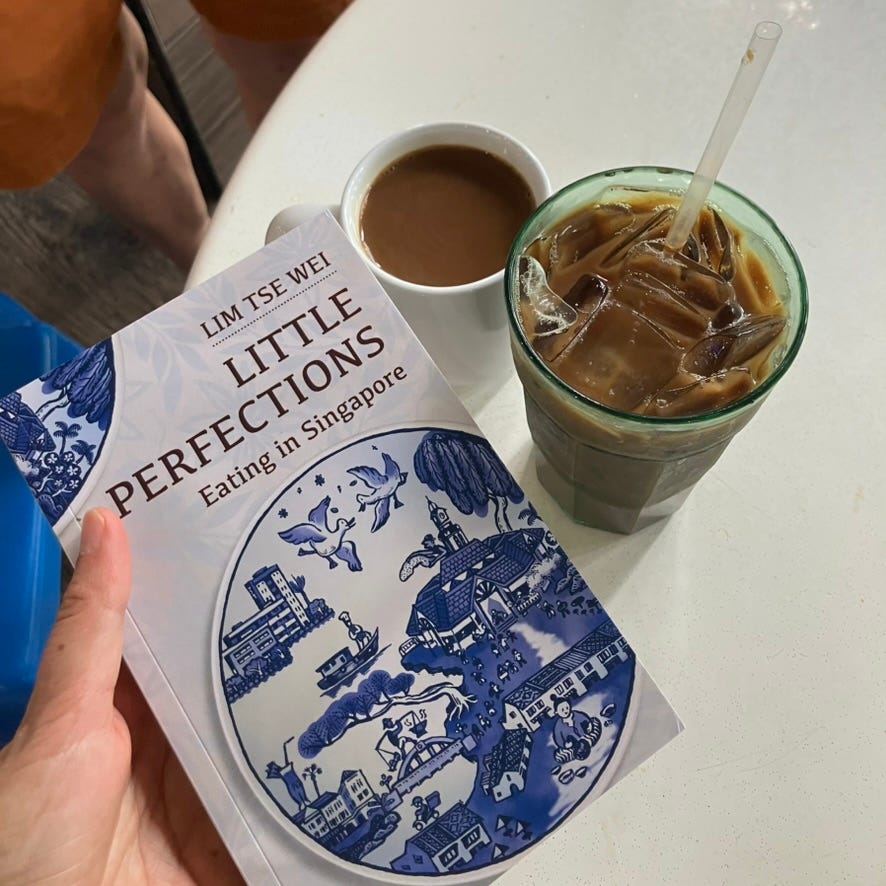

Little Perfections: Eating in Singapore enters the world tomorrow, Friday, Nov 14!

The only way I could be more excited about this is if you were to come to one of these events. Each time, I’ll be sharing the stage with someone far more articulate and famous:

Friday Nov 14, 6pm: What it means to eat in Singapore – a conversation with Christopher Tan at the Aliwal Arts Centre in Kampong Gelam.

Sat 15 Nov 4:30pm: Writing for flavour, writing for taste – a dialogue with Daryl Lim (more about writing - invite only, I can get you an invite), at a private venue in Boat Quay.

Sunday Nov 16, 3:30pm: It’s not just the rent: the business of food in Singapore – a conversation with my publisher, Goh Eck Kheng of Landmark Books, at Bookbar.

All free like beer, and also like speech. RSVPs unnecessary but appreciated, just hit reply.

As part of launch, I’m cooking a charity dinner for 40 tonight. It’s such a pleasure to have real chili padi and screaming fresh daun limau perut in the sambal belacan (more on real vs. ersatz chili padi, and sambal belacan).

And I’ve made a lot of loh kai yik over the last couple days (more on loh kai yik). The end is in sight, but we’re not there yet.

While hauling 5kg of pork and a whole lotta vegetables in Tiong Bahru market, I found a cheung fun place in Singapore that does it on trays (this is why I have cheung fun on the mind – but maybe thinking about cheung fun should just be part of my daily routine?).